Hey everyone,

In 2005, I was a 23-year-old writer from India who had figured out how to make a living writing for publications online. So, I wrote a book about it that I self-published and sold in pdf format.

The book did incredibly well, making me $10,000 in the first few months of its release and getting dozens of great reviews from writers, including so many that I respected and looked up to. One American writer who had written a book on freelancing herself wrote that mine beat any book she’d ever read on the subject, including her own!

All this praise. All the accolades. You’d have thought I’d be on top of the world.

Instead, my confidence was shattered and I was questioning why I had thought it a good idea to write the damn thing in the first place.

I’d had one bad review but to call it that would be to minimize what it actually was: a viscous personal attack on me on a massive platform, one of the biggest media websites in the world at the time. The American reviewer put me down on the basis that I was Indian, pooh-poohed my experience with some of the biggest Indian publications, and vilified me for trying to talk about freelancing when my experience was limited to India only (it was not but even if it had been, so what?)

I, a 23-year-old Indian writer had done something very few writers at the time had achieved, but in this woman’s American-centric, New York view of the world, none of that mattered. I was inconsequential to her because I didn’t look like, talk like, or publish like, her friends.

In 2020, this would be considered blatant racism but in 2005, it was considered perfectly acceptable and reasonable for a white woman to mock a 23-year-old Indian writer on one of the largest media websites in the world for being Indian and be applauded for her wit.

Of course, the Indian writer in question, me, believed her. I started questioning myself and before long, I’d put away all the other ideas I’d had for other books and even took that very book off the market. That I’d made a career, a living, out of doing something that very few people did, in a medium that was new and undiscovered, was special and worthy of being celebrated, but I couldn’t see that then. All I could see was what this woman had portrayed me to be– small, insignificant, stupid enough to feel like I could belong.

I didn’t publish any more books after that for ten years.

That wasn’t her fault, it was mine.

Who I believe and what I choose to believe about myself is my problem and not anyone else’s. I’d had hundreds of positive comments, including incredible reviews from writers around the world and my sales proved that people wanted what I had to offer, but I chose to believe the one attack on my identity and allow it to change my self-perception. That’s on me.

While I didn’t publish any more books, however, what this reviewer had inadvertently done was fire me up. I didn’t care how I did it, I was going to prove her wrong.

Before long, I’d had bylines in dozens of well-known publications, including all the major women’s magazines and many of the top newspapers and magazines in the world. I decided that no one was ever going to be able to tell me that I didn’t have the authority to speak on or write about anything and this early experience taught me something, more in hindsight than at the time, that I want everyone reading this to take away:

Your background, your experiences, your nationality, the color of your skin, all the things that make you who you are?

These are the things that make you special.

They are not your disadvantages; they are your superpowers.

Please, never allow someone to tell you that WHO YOU ARE is the reason you’re not or can’t be worth listening to. It’s the opposite– when you truly embrace the real you, that’s when your audience finds you, that’s when you attract like-minded editors, and that’s when your work truly has impact in the world.

It’s important that you remember this. What we believe about ourselves is how we show up in the world and for writers, who tend to be self-critical and introspective anyway, this can really hold us back. We are told repeatedly by the world that we are not enough and this is especially true for female and non-binary writers of color.

In 2002, the young college student from India couldn’t understand why her website, which readers loved and said offered more value than almost anything else out there, was never included in the “Best Of” lists, why many of the American writers online wouldn’t include her in their conversations, why she was kept outside of affiliate partnerships and promotional opportunities despite having one of the largest audiences in the space. In 2020, I understand how the world works but in 2002 I was naive enough to see the Internet as the great equalizer and believed that because people could only see my words through the computer screen, that would be the only thing they’d judge me by. I understand now that this is not the case; it was never the case.

A writing website I’ve tried to partner with several times make it a point to tell their readers just how expensive my courses are, though it is not a practice they apply widely to other writers they review. This is not a new experience for me. It was, until a few years ago, a regular occurrence for me, an Indian woman, to be told I was too expensive by editors and clients in the West while white writers were offered twice that amount by those same people without any resistance. (This doesn’t happen now as much thanks to social media and editors being called to account publically.)

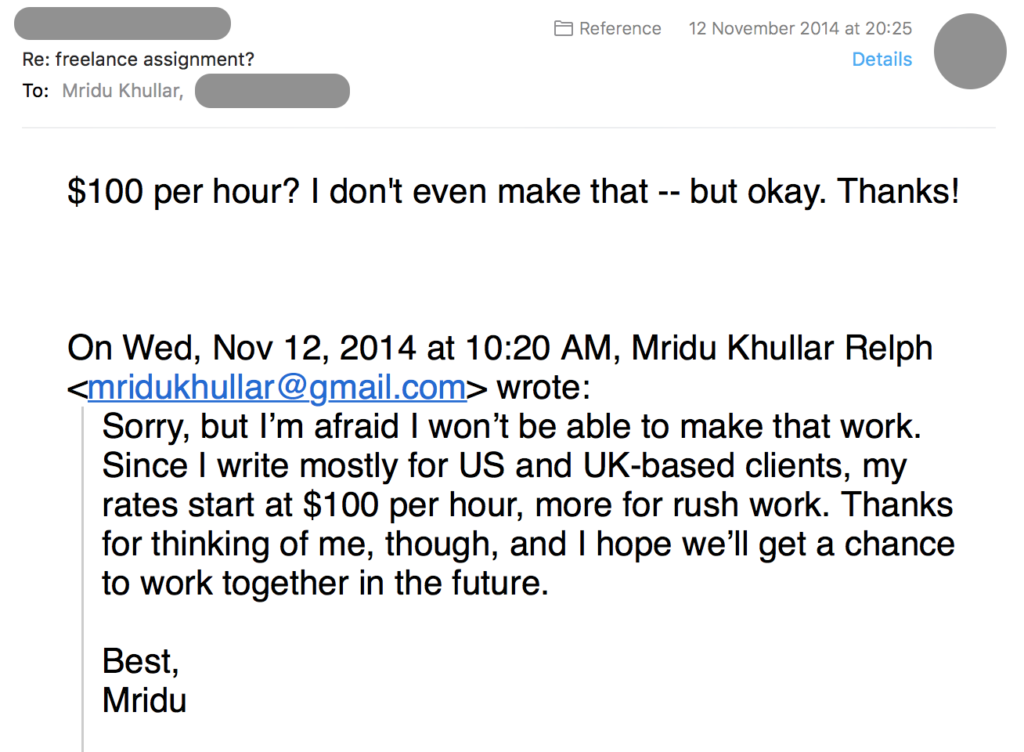

Six years ago I received this email from an editor at a major news website who had offered me an incredibly low rate for my work:

This editor, who also happens to be a woman of color, now mentors writers and is known as someone who really supports young talent. She supports freelancers making more money, you know, now that it’s in vogue for editors to be seen as treating writers fairly.

They not only think you’re inferior, they tell you that you are.

They believe it.

The problem is, you end up believing it, too.

And when you believe it, you don’t release books for ten years, you reduce the price of your products, you question your worth, all the while getting more and more isolated and wondering why you’re the bitch nobody likes.

You stop blogging, you start hiding, you stop telling the truth about the mindfuck the publishing and writing business is, the racism and sexism you experience so much of the time. The way they look down on you because they have such a low opinion of freelancers, that they can’t fathom your rates because even they, who deem themselves superior to you, don’t make that much.

You say nothing because you don’t want them to accuse you of playing the “victim card.” You don’t want them to reject you more than they already have.

It doesn’t AT ALL surprise me that my audience has such high numbers of writers who do not feel represented elsewhere. (100+ women have emailed me since I changed my name to tell me they’ve been thinking of changing theirs, too.)

In my stories of hating my name, you feel seen.

In my stories of being non-white and non-American and still managing to somehow make a good living at this thing, you find hope.

In my stories of failure, you find recognition.

In my stories of not belonging, you find representation.

You will always be too female, too gay, too Black, too Indian, too loud, too aggressive, too expensive, too something for some people.

Be it. Be it proudly. Let them believe whatever bullshit they will about you. Because they will.

Just you don’t go believing it too, okay?

Write those books, build those businesses, and charge whatever the fuck you want.

In doing so, you will find your true audience, your people, and they will love you for exactly who you are. Because that’s who they are, too.

I’m proof of it.

That you’re here, reading this, is proof of it, too.

Cheers,

Natasha